TONN INTERVIEWS: SUB-OBJECT

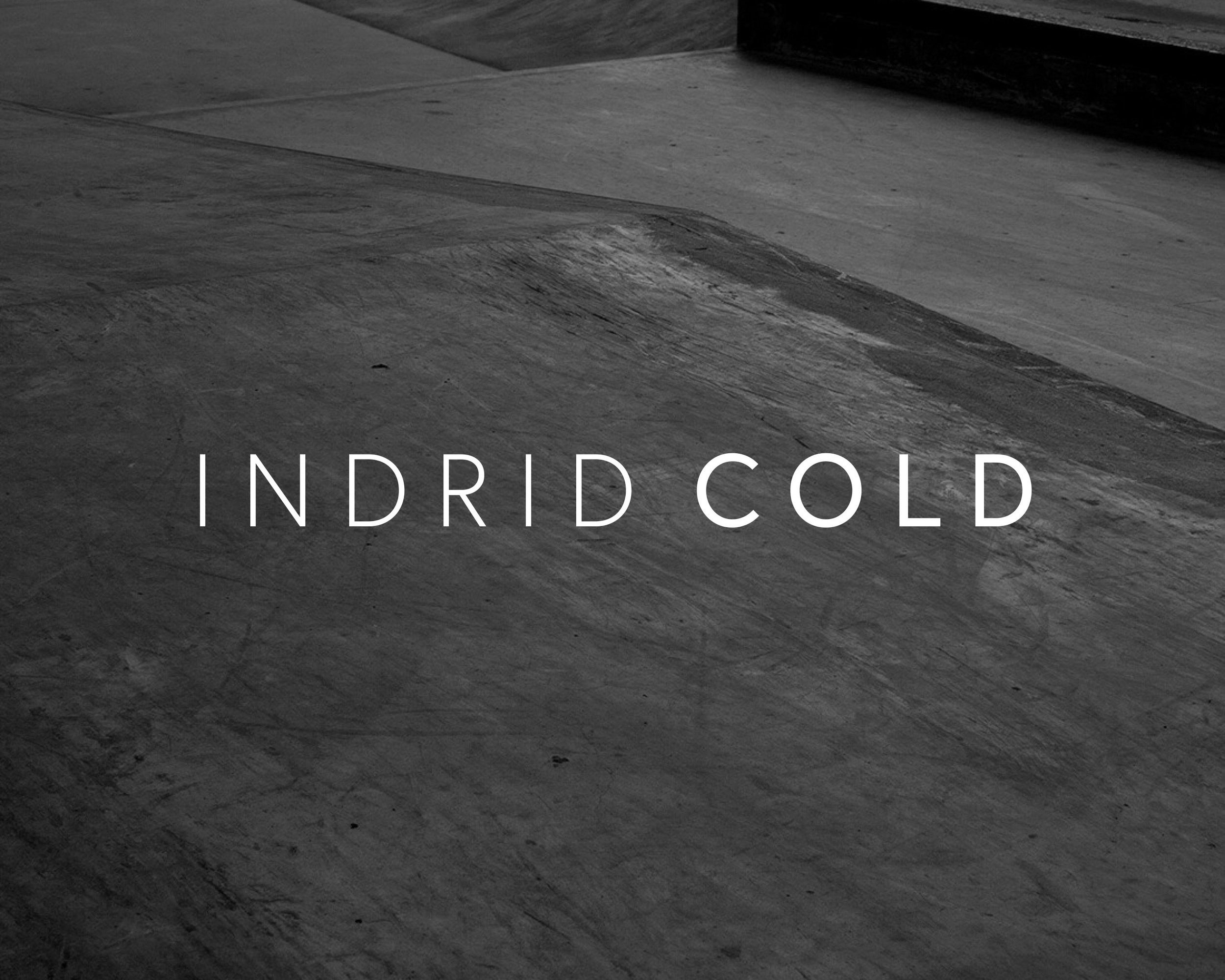

Above: ‘Modern Warfare’ © Mary McIntyre

Hugh Mulholland, Senior Curator of Belfast’s Metropolitan Arts Centre (The MAC), talks to Mary McIntyre about the collaborative process behind ‘Sub-Object’, the new album from Iv/An.

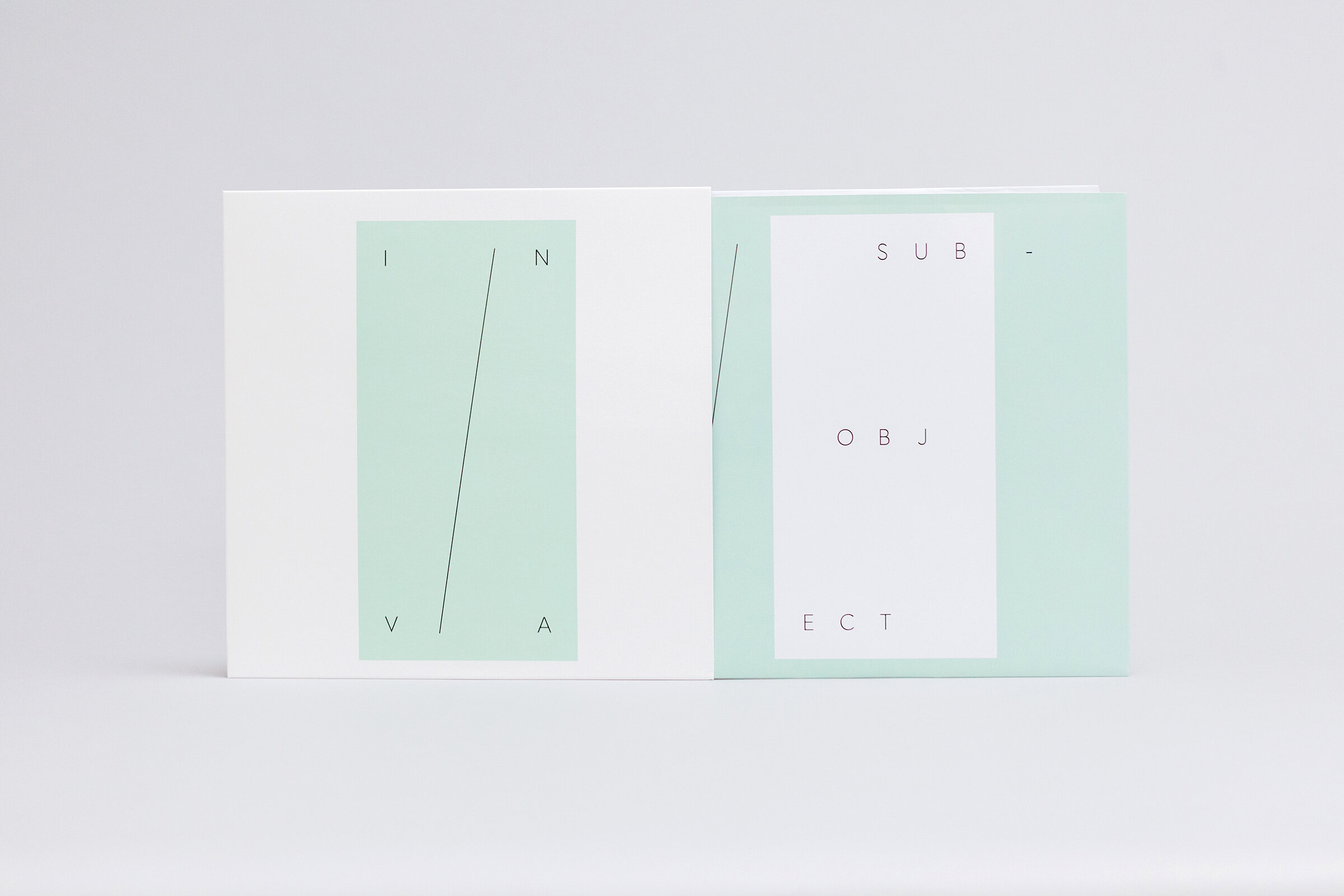

Hugh: Mary you’ve created a limited edition photographic print of your work to accompany Iv/An’s ‘Sub-object’ album. Is this the first time you have included an editioned print of your own artwork as part of a TONN release?

Mary: Yes, although we’ve produced a number of different types of limited editions on TONN Recordings, such as the special screen print for This Is The Bridge by artist Adam McIlwaine, as well as a number of limited edition vinyls and cassettes, this is the first time that I’ve created an edition that features my own artwork.

Hugh: How did this edition for Iv/An’s release come about?

Mary: Although I work alone as a visual artist, over the years I’ve become increasingly interested in collaborative practice. I’ve come to enjoy working with others more and more and recently, I’ve taken that a step further to explore how art forms can collaborate, or come into dialogue with one another. As part of that I’ve been looking at ways to draw out relationships between disparate art forms.

My work on TONN Recordings has led me to bring music into that conversation, to draw links and relationships between image, sound, text and interpretation. That’s what motivated the bringing together of Iv/An’s music, my photographic imagery and Frédéric Huska’s writing.

Hugh: Do you think your choice of producing a limited edition print for Iv/An’s album was influenced by your own experience as a visual artist, in the practice of producing artist multiples in fine art?

Mary: Yes, I think so. I’ve always appreciated the artist edition, the fact that it allows for an artwork to be produced at a smaller scale and as a fixed number of prints, decided at the beginning of the print run.

The number of limited editions is carefully chosen by the artist before production and no more can be created after they are all sold. When an edition is made in small numbers, as this TONN edition is, it’s a special thing, knowing that only 25 of these prints exist in the world. In a way an artist’s edition is very much like a limited pressing of a vinyl. Our TONN limited editions have always been produced in very small numbers and in a world of mass production, there’s something precious about that.

Hugh: For this limited edition print you’ve chosen your image, ‘Modern Warfare’. This photograph is typical of a body of work you have made of spaces devoid of the human figure. These photographs often seem to me to depict spaces, which have the feeling of an act, or action, that is about to take place, or has just taken place.

Mary: Yes ‘Modern Warfare’ came from a series of works that I made depicting municipal or institutional spaces. This image was originally produced and exhibited as a large-scale photographic work. This series of works, and indeed, many of my photographs, are devoid of the figure, but they evidence traces of human presence, through the objects and the architecture of the spaces I photograph.

That for me has always been a very important aspect of my work, that the sense of human presence lingers, despite the fact that in my photographs the spaces are often uninhabited. In making these works, I was drawn to the specifics of these places, the tiny details found in the fabric of the buildings, or the detritus left behind after their use. And at the same time, the sense of universality that these images convey, in so far as the furniture, which we see in the image ‘Modern Warfare’ for example, somehow seems to speak about human experience on a wider scale, of vulnerability, loss, solitary quietude, always in these images seen through the lens of the private individual within the public setting.

Hugh: Iv/An’s ‘Sub-object’ 12” vinyl has an inner sleeve, printed with a text written by photographer Frédéric Huska. I’ve exhibited Frédéric’s photographic work at the MAC in Belfast and as a curator, I was particularly interested in his approach to his photography, that he brought an additional dimension to it through his writing. When I was curating his exhibition, the writing that Frédéric had made around his own photographic images, to me seemed of equal importance to the images themselves. Reflective writing seems to be multi-faceted in a way that’s less straightforward than other narrative forms. Is that partly what led you to commission this text?

Mary: Yes, the reflective form is quite different from creative writing. It can contain fictional elements within it, if the writer chooses, but it’s distinct from fiction. It isn’t like story telling in that traditional sense. In Frédéric’s case, I was also interested in how he uses it as a way of reflecting on his own photographic process. Reflective writing lends itself well to photography, as it has an analytical aspect to it, which can offer insights into how we read a photographic image.

The first time I came across it in Frédéric’s work, was through the series of photographs he made called, ‘Location: Los Angeles’. Frédéric had taken a number of photographs in the city and then, at a later stage, gone back to those photographs and viewed them and made a written response to them in the third person. I found that an intriguing proposition, the idea of going back to photographs you had taken yourself, but stepping outside of your own authorship and viewing them as if through someone else’s eyes.

My student’s often ask me if it’s possible to be truly objective when looking at one’s own art and that can be a very difficult thing to do. Reflective writing I think, is the closest one might get to that. What was interesting in the case of Frédéric’s reflective writing, is the feeling that it spoke with a voice of someone viewing a photographic image for the very first time, as if the process of reflective writing allowed him to see his own work afresh. That’s what I think sets reflective writing apart from other forms, as it happens in the moment, like thinking through writing. To me it always feels like a process of discovery.

Hugh: How then did Frédéric come to the be writing about your photographs, beyond his own images?

Mary: Frédéric and I found that we had quite a similar approach to photography. In my work, as in his, we neither of us go looking for subjects. The subjects, tend to find us. When I choose to photograph a location, it’s because there’s something in the atmosphere of a place that resonates with me, in a way that I can’t ignore and when I’m photographing it, I feel as if I’m documenting an atmosphere, as much as I’m photographing a location. The aim of the photograph, in my work, is to capture the sense of a place, what one feels in it, as much as what one can see in it. So the location, and subsequently the image, become imbued with a psychological charge. It’s that sense of psychological charge that I also felt when I looked at Frédéric’s imagery.

So at some point, in our conversations about our work and photography, the idea of Frédéric further exploring reflective writing through taking on the challenge of responding to someone else’s photographs, instead of focusing solely on his own images, seemed to come as a natural development. But what became really interesting about his response to this particular image of mine, ‘Modern Warfare’, was that not only was his approach to reflective writing focused on my imagery instead of his own, but that in this case, it also became influenced by Iv/An’s music.

Hugh: That sounds like quite a complex task. How did the music get factored into this text as well?

Mary: Once Frédéric and I and Ivan had set about collaborating on this project, the three elements of image, music and text all seemed to co-exist in a very sympathetic way. I think Frédéric’s text is where the music and the image seem to come together in relationship with one another, as if there was a mirroring of image and sound going on. The landscape, or terrain that exists in Ivan’s ‘Sub-object’ compositions, is full of atmosphere, narratives of colour and textures.

The title of one of Iv/An’s album tracks seems to sum that up for me, ‘Tact as in tactile sound’. I feel listening to Iv/An’s ‘Sub-object’ that the sounds create the same sense of atmosphere and conjure a sense of place and psychological charge, in the same way that I set out to achieve in my photographs. So somehow, it felt as if Iv/An’s ’Sub-object’ and my ‘Modern Warfare’ image were crossing over in a very symbiotic way, to the extent that the tonal qualities in the photograph were echoed in Sub-object’s cover design.

As Frédéric started to write his text, focusing on my photographic image, he also then began listening to Iv/An’s album tracks. He told me that he became almost obsessed with ’Sub-object’, repeatedly listening to the music until it became intrinsically bound up in his writing, so that all of the elements of Iv/An’s sound and my image, became completely assimilated within his writing. That led him to come to not only describe the things that we see in the image, but also the music, as if sounds from Iv/An’s ’Sub-object’ had escaped the confines of his album and penetrated the room that I had pictured in my photograph, ‘Modern Warfare’.

“The sound resists against an obsolete system. It sneaks into the room and weaves in and out of the boards and trestles that look a bit like soldiers in rows. It breaks against the plastic covers on the walls and against the metal doors, it bounces back across the polystyrene-tiled ceiling and then numbs on the wooden floor. A few electric vibrations cut through this space that already carries within itself the announcement of its own dissolution. ”

Hugh: Something else that strikes me in Frédéric’s text, is the allusion to the human condition, the vulnerability of the body, its corporeality and its breaking down in illness. That seems to chime with the times we are living through. Did the pandemic in anyway influence it do you think?

Mary: Actually the text had nearly been completed just before the pandemic struck. But I think what it does is reveal, is a ripple effect of human trauma that is coming through the photograph. When I made that photograph, I titled it, ‘Modern Warfare’ because the image was heavily influenced by the Bosnian crisis that we had witnessed in the 90s.

During that period, many television news reports documented the temporary shelters that were erected to house displaced people who were fleeing from the violence that was unfolding in Europe at that time. These shelters were often set up in large municipal buildings, such as sports arenas, with row upon row of camp beds and make-shift medical paraphernalia.

I couldn’t get those images out of my head. So some years later, when I took that photograph, that was uppermost in my mind. Even if one did not know of the particular context of my ‘Modern Warfare’ image, one could not fail to recognise a sense of the frailty of human existence in such a setting, that is in so many ways, a hostile environment. I won’t go on to further dissect the image, I prefer people to have their own response to the work.

But it’s clear that Frédéric’s text explored the very thing we have been speaking about here, in alluding to that which I often deliberately leave out of my photographs - the human figure. Frédéric makes the absence of the figure in the photograph, present in his text and in that space, in a very visceral way. And I think that brings us back to precisely your point, that the sense of human frailty is palpable in that, in a way that resonates with us today, now more than ever.

“What do you do with your body when it’s forced to lie still, flat, pressed against the floor, against a stretcher, against an operating table, when it’s rendered useless, when it’s injured, when it’s pierced? It would seem to me a little strange, enigmatic, fascinating, but also sad.”

Frédéric Huska is a photographer and writer based in Ireland.

fredhuska.wordpress.com

Hugh Mulholland is Senior Curator of Belfast’s Metropolitan Arts Centre (The MAC).

themaclive.com